Diet Drugs of the Past

A History of Weight Loss Missteps

Over the past 90 years, there have been several attempts to develop and market diet drugs to help with weight loss. However, many of these attempts have ended in failure due to various reasons, including safety concerns, lack of effectiveness, and unforeseen side effects.

With new drugs like Ozempic / Wegovy and Mounjaro being prescribed so much they’re experiencing shortages, I thought I’d look back at other blockbuster diet drugs of the past. Here are some notable examples of diet drug failures:

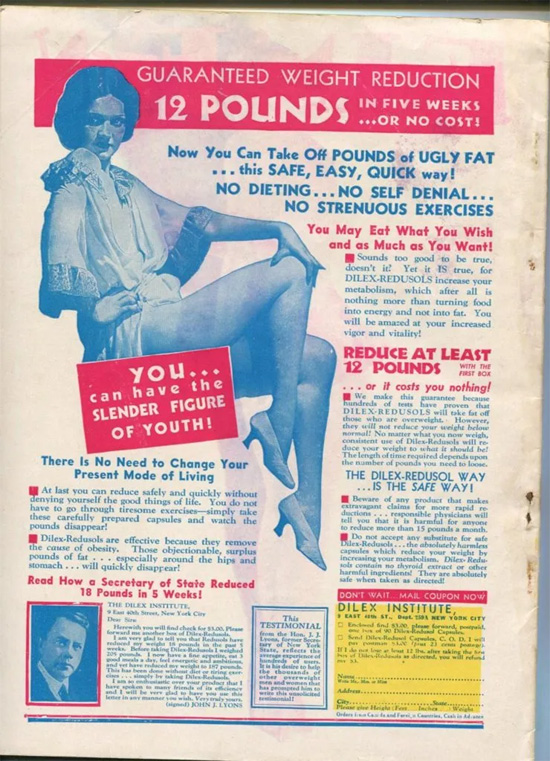

Dinitrophenol (DNP) The Body-Burning Bomb: In the 1930s, DNP was marketed as a weight loss drug that increased metabolism by causing the body to burn more calories. But what it actually did was turn people into walking furnaces, causing skyrocketing body temperatures, a racing heart, and even death in some cases. DNP was eventually banned for human consumption due to its dangerous side effects.

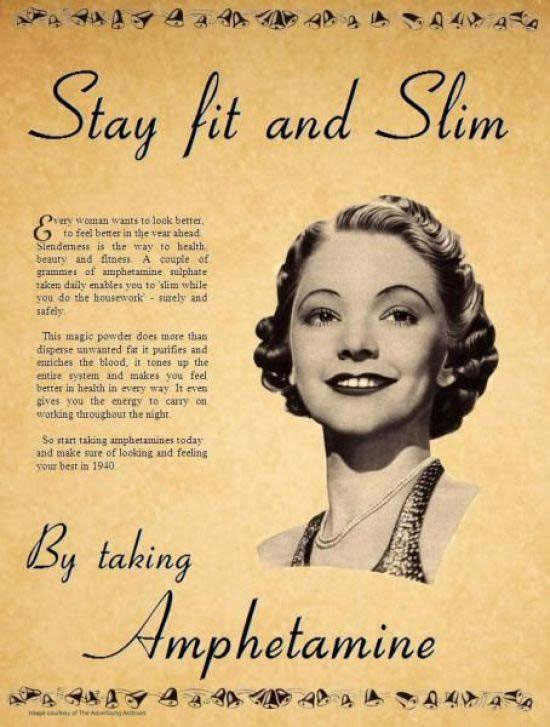

Amphetamines were first synthesized in the late 19th century, but it wasn't until the 1930s that their appetite-suppressing properties were recognized. Starting in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s and 1970s, amphetamines and amphetamine-like drugs were widely prescribed by doctors as diet pills or appetite suppressants to aid in weight loss.

Brands like Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine) and Benzedrine became popular weight loss aids, and they were marketed to the general public with little oversight or concern for potential misuse. Their popularity grew, in part, because they not only suppressed appetite but also boosted energy and mood, making them attractive to users.

However, as awareness grew about the potential for addiction, the harmful side effects, and the risk of misuse, regulations around the prescription and sale of amphetamines became more stringent. In the United States, the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 classified amphetamines as Schedule II drugs, acknowledging their high potential for abuse and limiting their prescription for weight loss.

Have you see this ad for ampheatmines? Well it's a fake. The image is actually an altered version of an 1939 ad for Bile beans, a laxative and tonic of questionable repute.

Fen-Phen: In the 1990s, a combination of two drugs, fenfluramine and phentermine (known as Fen-Phen), was prescribed for weight loss. It was the the dynamic duo that seemed like a match made in weight loss heaven. While it initially showed promise, it was later linked to serious heart and lung problems, leading to the withdrawal of fenfluramine from the market.

Meridia (Sibutramine): Meridia was approved in the late 1990s as an appetite suppressant. It was supposed to be the trustworthy friend that helped you keep your cravings in check. But it turned out to be more like that unreliable pal who always shows up late. Over time, it was found to increase the risk of heart attack and stroke, leading to its withdrawal from the market in 2010. But a lot of people may be taking it and not knowing. When the FDA examined diet supplements in 2018, they found sibutramine in over 700 of those supplements marketed as “natural,” “traditional,” or “herbal remedies.”

Rimonabant (Acomplia): Rimonabant was designed to help people lose weight by blocking receptors in the brain associated with hunger. It was associated with an increased risk of psychiatric side effects like depression and anxiety, leading to its withdrawal from the market in several countries.

AFP/Getty Images

Qsymia: Qsymia was a combination of two existing medications, phentermine and topiramate, intended for weight loss. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initially rejected its approval in 2010 due to concerns, but they eventually approved it for use in the United States. Qsymia has never been approved in Europe. It is believed to cause birth defects, and the side effects include elevated heart rate and increased risk of heart attack and stroke, all for an average weight loss of 10-11%.

Belviq (Lorcaserin): Belviq was approved in 2012. It seemed like a friendly companion, acting on serotonin receptors to keep those food cravings at bay. But as it turns out, this friendship wasn’t meant to last. In 2020, Belviq was voluntarily withdrawn from the market due to concerns about potential cancer links. That’s especially problematic since once you started Belviq, you were supposed to take it for the rest of your life.

Contrave: Contrave is a combination of two medications, naltrexone and bupropion, which were approved for weight loss in 2014. Here’s what Consumer Reports said about it:

“In three clinical trials, people who took Contrave up to 56 weeks lost only five to nine pounds more on average than those who took a placebo. And Contrave can cause serious side effects, such as liver damage, seizures, and possible heart risks. That’s why Consumer Reports’ medical advisers say most people should skip it: such a small amount of weight loss is not worth the risk of those possible side effects.”

These examples illustrate the challenges in developing effective and safe weight loss drugs. Weight management is a complex issue influenced by genetics, lifestyle, and individual responses to medications. Billions of dollars and decades of research have led to dozens of failures.

But now there’s something new. A class of drugs that target GLP-1 receptors that have had over 6 million prescriptions written in just the first five months of 2023. Click here for part 2.

Part 1 2 3

Call for a FREE Consultation (305) 296-3434

CAUTION: Check with your doctor before

beginning any diet or exercise program.

8/21/2023

Updated 10/25/2023